How Marcel Proust Is Going Digital

The University of Illinois commemorates the centennial of the First World War by digitizing the work of Marcel Proust.

Hours

before Germany formally declared war on France in WWI, Marcel Proust

penned a letter to his financial advisor that anticipated the horrors to

come. He wrote:

“In

the terrible days we are going through, you have other things to do

besides writing letters and bothering with my petty interests, which I

assure you seem wholly unimportant when I think that millions of men are

going to be massacred in a War of the Worlds

comparable with that of [H. G.] Wells, because the Emperor of Austria

thinks it advantageous to have an outlet onto the Black Sea.”

This letter, composed the night of August 2, 1914 and digitized in the online exhibition Proust and the Great War, offers a unique glimpse into the mind of one of France’s preeminent writers on the eve of war to end all wars. As part of a cross-campus initiative

at the University of Illinois, this exhibition puts project-based

learning into practice: a semester-long effort by François Proulx,

assistant professor at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and

his graduate students to curate, digitize, contextualize, and translate

Proust war correspondence.

The

exhibition provides a glimpse at a longer, ongoing digitization effort

at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Thanks to a partnership

with the French Cultural Services and Centenary Commission, faculty,

staff, and students will make hundreds of rare letters written between

1914 and 1919 publicly available next fall in Marcel Proust’s World War I Letters: A Digital Edition. While this project will be a boon to Proust scholars and World War I historians, its stakes should interest a range of online learning practitioners and enthusiasts.

How

can literature help us to commemorate, recollect, and reevaluate war?

What should a scholarly edition look like in the 21st century? And how

might that digital version exceed its print counterpart?

WWI Today

World

War I often takes a backseat to World War II in American historical

memory. This raises obstacles for those seeking to commemorate the

centennial of U.S. entry into the war (April 6, 1917). Bénédicte de

Montlaur, cultural counselor of the French Embassy, acknowledged that

challenge during our conversation about the Proust digitization effort.

“The

First World War is not present in the public memory here as it is in

France, but that’s why we think it’s important to focus on how this war

shaped international affairs,” she explained. “It marks the beginning of

the United Nations, and it’s when America became a superpower.”

The French Embassy has planned a host of events to commemorate the centennial, including concerts, conferences, film screenings, and, of course, the sponsorship of Marcel Proust’s World War I Letters: A Digital Edition.

The

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, which possesses one of the

largest collections of Proust manuscripts, is a natural partner for the

French Embassy as it seeks to reinforce ties between French scholars,

intellectuals, artists and their American counterparts. (Montlaur noted

that the embassy is also collaborating with Columbia University, Duke

University, NYU, Texas A&M University, and UCLA on other centennial

commemoration projects.)

“Proust is the French author everyone refers to. He’s our Shakespeare. He’s our Goethe,” explained Montlaur.

Commemorating

World War I using Proust correspondence doesn’t just serve the

interests of Proust scholars; it also mobilizes their interest to draw

new attention to the war. Proust’s letters lend texture to the

experience of war, and challenge mechanized associations with flashes of doubt, despair, and reverence.

In a March 1915 letter,

Proust recollects: “I went outside, under a lucid, dazzling,

reproachful, serene, ironic, maternal moonlight, and in seeing this

immense Paris that I did not know I loved so much, waiting, in its

useless beauty, for the onslaught that could no longer be stopped, I

could not keep myself from weeping.”

In letter from that summer,

he laments: “We are told that War will beget Poetry, and I don’t really

believe it. Whatever poetry had appeared so far was far unequal to

Reality.” (I would be remiss if I didn’t note that Proulx’s graduate

students, Nick Strole and Peter Tarjanyi, curated and translated these

letters.)

Proust’s

letters remind us of the human costs of warfare and articulate doubt

that we rarely permit preeminent authors. A digital edition of that

correspondence could help de-monumentalize Proust, making him more

accessible to scholars, educators, and learners.

The Kolb Edition

To

appreciate the digital edition to come, one must understand how Proust

was studied before. The de facto edition of Proust is a 21-volume

edition of letter edited by Philip Kolb,

a professor of French at the University of Illinois. Published between

1970 and 1993 — shortly after Kolb’s death — this edition represents his

life’s work.

The

Kolb edition is remarkable in its scope and ambition. In addition to

collecting all of the letters available at the time of publication (more

than 5,300), he also seeks to place them into chronological order. This

is no small feat given that Proust didn’t date letters. (There was no

need because letter writing was a daily activity and the envelopes

included postage marks.) Kolb spent most of his professional life

performing inferential detective work. For example, if Proust mentioned

foggy weather in a letter, Kolb would find the weather report from the

month in order to infer or at least narrow the date. He recorded all of

this contextual material, what we would call metadata, on index

cards — more than 40,000 in total.

As

Caroline Szylowicz, the Kolb-Proust librarian, curator of rare books

and manuscripts and associate professor at the University of Illinois,

explained it, Kolb effectively created a paper-based relational database.

He created files for every person mentioned in correspondence, file

identifiers for each letter, and even a complete chronology of Proust’s

social life.

In

the 25 years since the publication of the last volume, more than 600

letters have surfaced in auction catalogues, specialized journals, and

books. (The collections at the University of Illinois have increased

from 1,100 at the time of Kolb’s death to more than 1,200 today.) Those

letters are valuable in their own right, but they also change the way

scholars understand the existing corpus. For example, a new letter might

include information that revises previous chronology.

It’s

no longer feasible to produce an updated Kolb edition. For a number of

institutional reasons, faculty are no longer encouraged to produce vast

scholarly editions, no less work that requires decades to produce. Publishers aren’t eager to print multi-volume editions for a limited audience.

“With

the steady appearance of rediscovered or newly available letters, a new

print edition would be out of date within a few decades,” explained

Proulx. “Also, a 20-volume edition would be prohibitively expensive for

individual readers, and mostly only available in research libraries.”

A

digital edition, on the other hand, doesn’t need a publisher, and it

can expand to accommodate new letters and context as it becomes

available. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library began

the digitization process immediately after Kolb’s death: Szylowicz, in

particular, marked up (using TEI) Kolb’s research notes and documentation to make them electronically available via the Kolb-Proust Archive. Marcel Proust’s World War I Letters willextend that work by digitizing hundreds of his actual letters.

Toward a Digital Edition

While

the Proust Digital Edition won’t be available until next

fall — sometime before the end of the centennial on November 11,

2018 — readers can expect that it will look something like the Proust

and the Great Waronline exhibition that I cited at the beginning of this

piece.

Unlike

the Kolb edition, which was published entirely in French, the digital

edition will accommodate transcriptions and English translations, which

Proulx and Szylowicz will solicit through an open-source crowdsourcing

platform developed by their partners at the Université Grenoble Alpes.

Whereas scholars used to format the exact text to show a finished state

(what’s called a linear transcription), today many scholars seek to

reveal the process of writing by including marginalia and emendations

(diplomatic transcription). The crowdsourcing platform will accommodate

both forms of transcription simultaneously, allowing readers to see the

unfinished aspects of Proust’s writing. This technical choice may enable

scholars to read his work differently: Proust often added or clarified

his remarks in postscript that might not otherwise be visible in a

linear transcription.

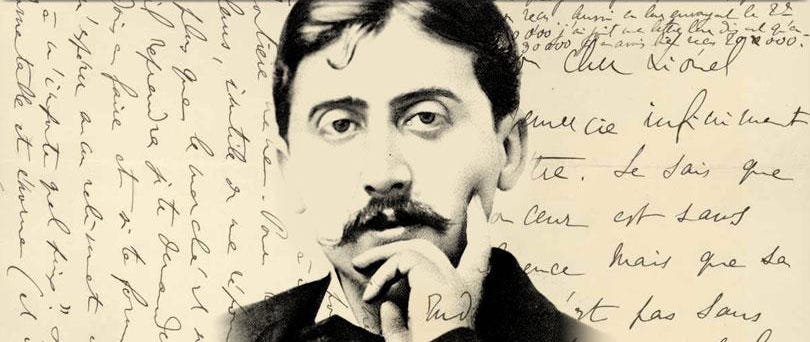

The digital edition will also allow readers to see Proust’s hand through scans of letters. In addition to conveying a sense the aura

of a letter (as a material object), a digital copy allows a reader to

attend to the conditions of his writing. “Proust’s letters are often

somewhat messy,” explained Proulx. “His handwriting is frequently

difficult to read, he sometimes scribbles in the margins or even between

lines. Images, when they are available, give a better sense of the

letter as its recipient would have experienced it: an often-hurried

missive from a complicated man.”

“Proust’s

penmanship evolves over time, from childhood letters, to his ‘dandy’

years, when he consciously starts to develop a distinctive hand, with

curious c’s that extend under the following letters,” added Szylowicz.

“In the last weeks of his life, Proust, who is then weakened by asthma

and pneumonia, is unable to speak and reduced to writing little notes to

[his caretaker] on scraps of paper or the back of letters, in a

distinctly shaking hand.” (Reference an example here.)

The

availability of images and different transcription practices provide

new ways of experiencing Proust that undermine the notion of a

monumental author, but also reveal, in the words of Proulx, a

complicated man. Authors must be granted moments of frailty: to deny

them that is to deny them humanity and to practice hagiography.

Finally,

and perhaps most importantly, a digital edition invites new

participants into textual editing. That is, while Kolb’s edition has

served scholars well, the complexity of a digital edition demands new

forms of expertise and participation: that of curators, researchers, and

scholars, certainly, but also that of technologists, transcribers,

translators, and students. Enlisting students in the editing process

isn’t just a useful pedagogical exercise; it will likely produce new

discoveries, as Proulx and his students demonstrate with their online

exhibition.

Read more: “The Met Makes Public-Domain Artifacts Free to Use”

No comments:

Post a Comment